- Covered:

- Key Terms:

- proper sampling, aliasing

- Nyquist / Shannon sampling theorem

- Nyquist frequency / rate

- impulse train

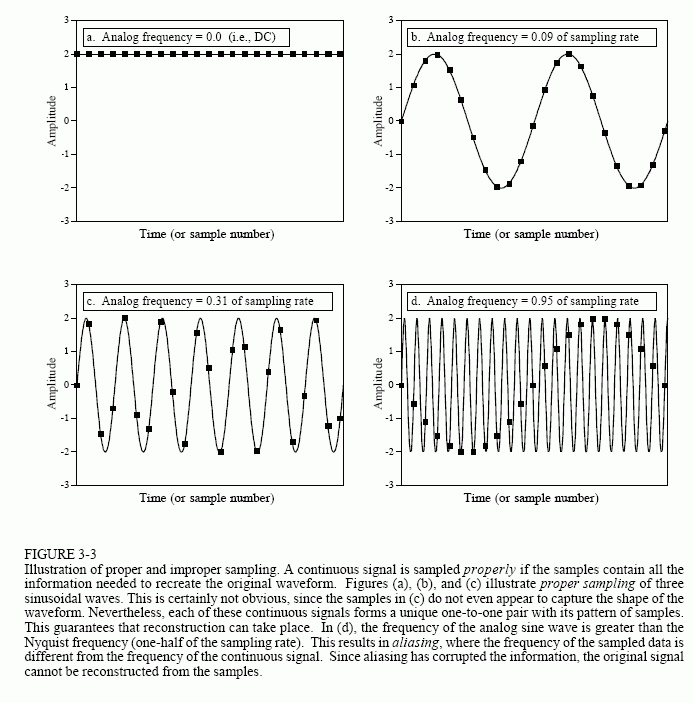

What is proper sampling? A continuous, analog signal is properly sampled if you can exactly reconstruct the original signal from the samples. But this gets subtle! Three out of the four below are properly sampled because the samples correspond to exactly one original signal, e.g. the sampling has captured enough information to reverse the sampling process. But in (d), the last one, the samples do not represent the original signal, because they can essentially be confused with a different signal! This is called aliasing.

This gets at a big DSP theorem, the sampling theorem, also known as the Shannon sampling theorem or Nyquist sampling theorem. It says the following:

…a continuous signal can be properly sampled, only if it does not contain frequency components above one-half of the sampling rate. For instance, a sampling rate of 2,000 samples/second requires the analog signal to be composed of frequencies below 1000 cycles/second.

This basically reflects the aliasing problem - you don’t want your samples to accidentally hide (alias!) some faster signals! This is part of why our basic sampling rate is at 44100Hz (in addition to historical / technical constraints) - the threshold of human hearing is around 20kHz.

You’ll hear the terms Nyquist frequency / Nyquist rate referred to, but they’re not well defined. This book chooses to define them as one-half the sampling rate, which is the frequency that the original signal must not contain frequencies above.

Aliasing will turn higher frequencies into lower ones, meaning you lose information about both the higher AND lower frequencies. If you have a sampled frequency at 3000Hz from an improperly sampled signal (e.g. Nyquist rate < 6kHz or analog signal contains high frequencies), that frequency might’ve come from an aliased frequency at 9kHz, 12kHz, 18kHz, who knows! So you lose the original high, and create an artificial low. Even worse - aliasing can create phase shifts too, depending on the relationship between the Nyquist rate and the original signal!

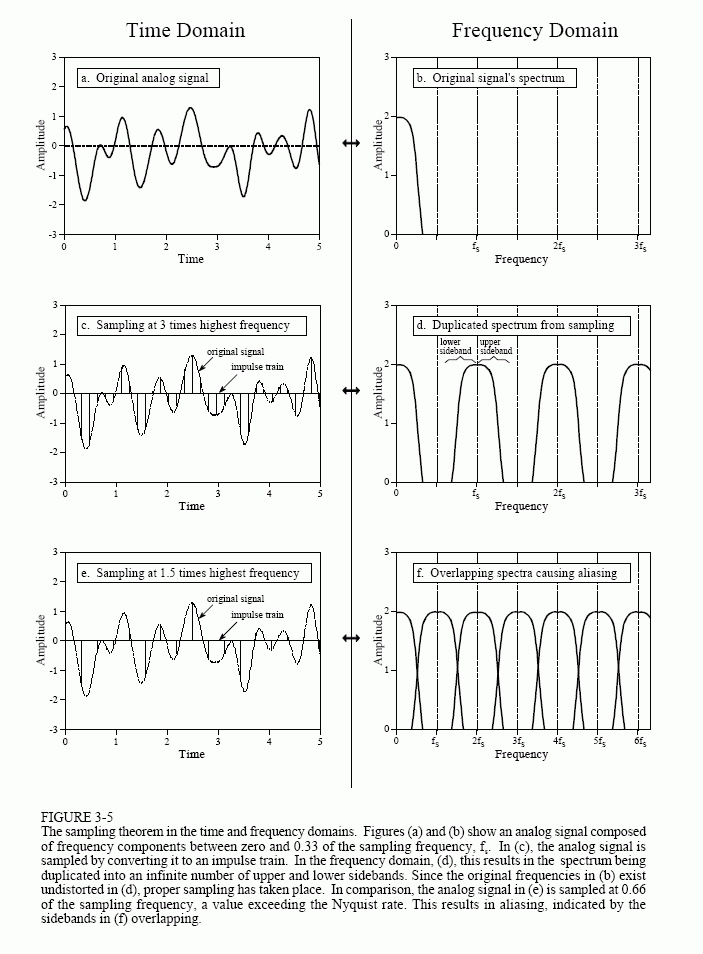

How do we actually sample? We use the theoretical concept of an impulse train to get at it, where we have a continuous signal whose amplitude is zero except at sampling points, when it spikes to match the amplitude of the analog signal.

This sampling process generates a frequency spectrum that matches the original when properly sampled, but it also generates upper and lower sidebands at whole number intervals to the sampling frequency. We can remove these with a low-pass filter, so the sampling is still proper despite frequency duplication. When we improperly sample, these sideband frequencies actually overlap, making it impossible to determine the actual original frequencies:

Why do these sidebands get generated? It has something to do with convolutions and two time domain signals (the original + the impulse train) being convolved. But this is beyond my current understanding and will be explained more in later chapters.